NEW YORK — “Dead Outlaw,” the offbeat musical from the team behind the Tony-winning musical “The Band’s Visit,” isn’t mincing words with the title. The show, which had its official opening Sunday at Broadway’s Longacre Theatre, tells the story of the unsuccessful career of a real-life bandit, who achieved more fame as a corpse than as a man.

Born in 1880, Elmer McCurdy, a crook whose ambition exceeded his criminal skill, died in a shoot-out with the police after another botched train robbery in 1911. But his story didn’t end there. His preserved body had an eventful afterlife all its own.

“Dead Outlaw,” a critics’ darling when it premiered last year at Audible’s Minetta Lane Theatre, may be the only musical to make the disposition of a body an occasion for singing and dancing.

David Yazbek, who conceived the idea of turning this stranger-than-fiction tale into a musical, wrote the score with Erik Della Penna. Itamar Moses, no stranger to unlikely dramatic subjects, compressed the epic saga into a compact yet labyrinthine book. Director David Cromer, whose sensibility gravitates between stark and dark, endows the staging with macabre elegance.

Yet Yazbek, Moses and Cromer aren’t repeating themselves. If anything, they’ve set themselves a steeper challenge. “Dead Outlaw” is more unyielding as a musical subject than “The Band’s Visit,” which is to say it’s less emotionally accessible.

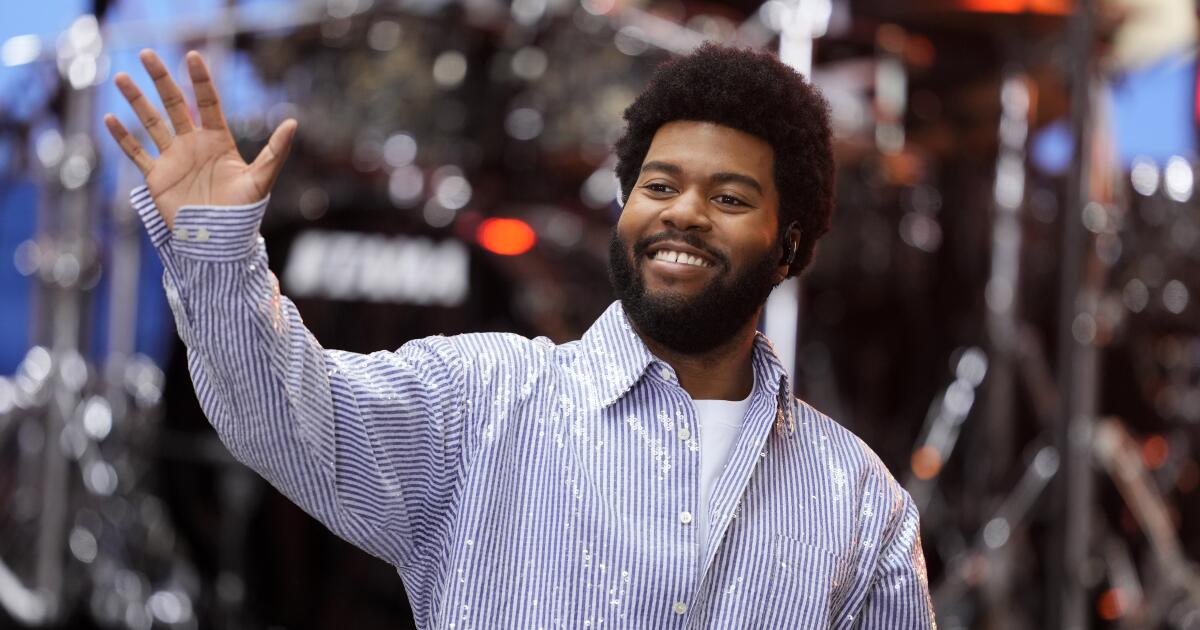

Andrew Durand stars in “Dead Outlaw.”

(Matthew Murphy)

It’s not easy to make a musical about a crook with a volatile temper, an unslakable thirst for booze and a record of fumbled heists. It’s even harder to make one out of a dead body that went on exhibition at traveling carnivals and freak shows before ending up on display in a Long Beach fun house, where the mummified remains were accidentally discovered by a prop man while working on an episode of “The Six Million Dollar Man” in 1976.

Stephen Sondheim might have enjoyed the challenge of creating a musical from such an outlandish premise. “Dead Outlaw” evokes at moments the droll perversity of “Sweeney Todd,” the cold-hearted glee of “Assassins” and the Brechtian skewering of “Road Show” — Sondheim musicals that fly in the face of conventional musical theater wisdom.

As tight as a well thought-out jam-session,”Dead Outlaw” also recalls “Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson,” the Michael Friedman-Alex Timbers musical that created a satiric historical rock show around a most problematic president. And the show’s unabashed quirkiness had my theater companion drawing comparisons with “Hedwig and the Angry Inch.”

Andrew Durand, who plays Elmer, has just the right bad-boy frontman vibe. The hard-driving presence of bandleader and narrator Jeb Brown suffuses the production with Americana authenticity, vibrantly maintained by music director Rebekah Bruce and music supervisor Dean Sharenow.

Elmer moves through the world like an open razor, as the title character of Georg Büchner’s “Woyzeck” is aptly described in that play. A précis of Elmer’s early life in Maine is run through by members of the eight-person cast in the bouncy, no-nonsense manner of a graphic novel.

The character’s criminal path is tracked with similar briskness — a fateful series of colorful encounters and escapades as Elmer, a turbulent young man on the move, looks for his big opportunity in Kansas and Oklahoma. Destined for trouble, he finds it unfailingly wherever he goes.

Elmer routinely overestimates himself. Having acquired some training with nitroglycerin in the Army, he wrongly convinces himself that he has the know-how to effectively blow up a safe. He’s like a broke gambler who believes his next risky bet will bring him that long-awaited jackpot. One advantage of dying young is that he never has to confront his abject ineptitude.

Arnulfo Maldonado’s scenic design turns the production into a fun-house exhibit. The band is prominently arrayed on the box-like set, pounding out country-rock numbers that know a thing or two about hard living. The music can sneak up on you, especially when a character gives voice to feelings that they can’t quite get a handle on.

Thom Sesma in “Dead Outlaw.”

(Matthew Murphy)

Durand can’t communicate emotions that Elmer doesn’t possess, but he’s able to sharply convey the disquiet rumbling through the character’s short life. There’s a gruff lyricism to the performance that’s entrancing even when Elmer is standing up in a coffin. But I wish there were more intriguing depth to the character.

Elmer is a historical curiosity, to be sure. And he reveals something about the American moneymaking ethos, which holds not even a dead body sacred. But as a man he’s flat and a bit of a bore. And the creators are perhaps too enthralled by the oddity of his tale. The show is an eccentric wallow through the morgue of history. It’s exhilarating stylistically, less so as a critique of the dark side of the American dream.

Julia Knitel has a voice that breaks up the monochromatic maleness of the score. As Maggie, Elmer’s love interest for a brief moment, she returns later in the show to reflect on the stranger with the “broken disposition” who left her life with the same defiant mystery that he entered it. I wish Knitel had more opportunity to interweave Maggie’s ruminations. The unassuming beauty of her singing adds much needed tonal variety.

The musical takes an amusing leap into Vegas parody when coroner Thomas Noguchi (an electric Thom Sesma) is allowed to strut his medical examiner stuff. Ani Taj’s choreography, like every element of the production, makes the most of its minimalist means.

Wanderingly weird, “Dead Outlaw” retains its off-Broadway cred at the Longacre. It’s a small show that creeps up on you, like a bizarre dream that’s hard to shake.