Alice Forward

Alice ForwardA group of racially diverse artists invited to reinterpret a touring British Museum collection with links to slavery have raised issues around payment, representation and emotional support.

The group said while they were pleased to take part in the “important” work on show at Ceredigion Museum in Aberystwyth, there were “challenges”.

“I don’t want to dismiss the positive efforts that individuals and institutions are making – it is just that we and they need to think about how we do it,” said one of the artists Déa Neile-Hopton.

The British Museum said it was gathering feedback and “learnings from this will contribute to future projects”.

The Trustees of the British Museum

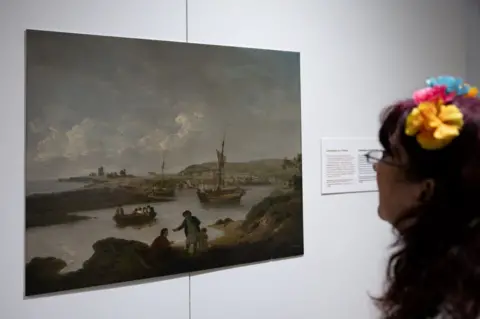

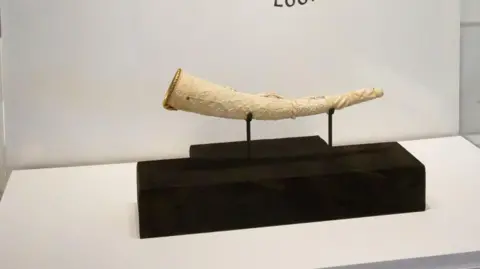

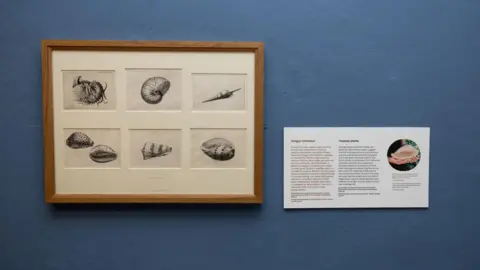

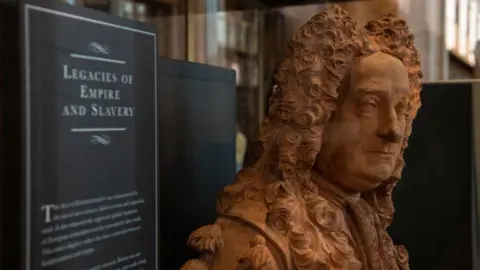

The Trustees of the British MuseumThe British Museum’s touring exhibition “For the curious and interested” features objects collected by physician and naturalist Sir Hans Sloane.

Sloane worked as a doctor on slave plantations and, with assistance from both English planters and enslaved West Africans, assembled a collection of 800 plant specimens as well as animals and curiosities.

He later married Elizabeth Langley Rose, heiress to sugar plantations in Jamaica worked by enslaved people, profits from which contributed substantially to his ability to collect in the ensuing years.

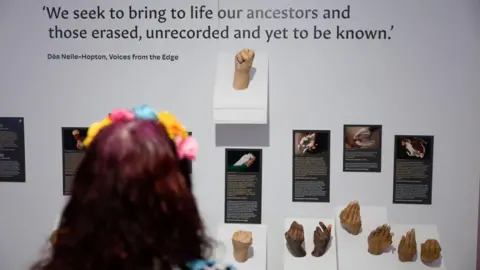

Voices from the Edge, a group based in mid and west Wales, produced creative responses, such as drawing and sculpture, to be shown alongside the collection’s touring exhibition which is currently at Ceredigion Museum until 7 September.

“Something we all felt very aware of was that all the representatives of the museum and the design team and everybody that had a professional role in the project were white-bodied people,” said basket weaver Déa.

“Sometimes it did feel a little bit like oh here we go again in the same pattern – we’re the unpaid workers yet again and we’re being asked to try to do this really difficult challenging work.”

She said they had been given an attendance fee of £50 per day for when they had to travel “but all the very many hours outside of that day were not covered and obviously £50 a day is not a wage is it”, she added.

The museum said the touring exhibition partner – in this case Ceredigion Museum – had agreed a participation fee with community participants in advance of their involvement and they were reimbursed for any travel expenses incurred. It said additional funding for the group was provided by the Association of Independent Museums (AIM).

It added it had been agreed that the artworks created by the group would be returned after the exhibition.

The Trustees of the British Museum

The Trustees of the British MuseumArtist Abid Hussain said he found the whole process highly emotional.

He said his heritage was “unrecorded and unknown” and he did not know his date of birth.

“I am a refugee, I am a queer person and I’m a person of colour,” he said.

Along with the rest of the group, Abid visited to the British Museum in London for a private viewing of the objects.

He said of seeing the collection: “I felt vulnerable… I started crying a little bit.”

His creative response to the collection was a video in which he repeats the phrase “my voice is not working” over and over again.

What did he mean by that?

“The meaning is that when you’re taking on an opportunity like this and you are dealing with these very difficult and emotional issues, sometimes you feel like your voice is not working when it comes to expressing your ideas,” he said.

“You see yourself on the walls because there is that attitude that black and brown skin should be included but when it comes to intellectual opinions your voice is not working.

“It’s very much an aesthetic-led process to me.”

He said during the project he had two therapy sessions with a Voices from the Edge member who is a trained therapist.

“It’s not just an art project, I think it’s more than that. You can get very hurt in the process so I think care systems should be in place.”

The Trustees of the British Museum

The Trustees of the British MuseumVoices from the Edge member Mina Katouzian, who was born in the UK and is from Iranian background, said she was also in tears on the visit to the British Museum.

“Suddenly I was questioning everything,” she said.

She thinks the British Museum may not have anticipated the emotional toll the project would take on participants.

“This wasn’t foreseen in the creation of the project,” she said.

“How long-term some of this impact can be and where it can go wasn’t really thought through.”

British Museum

British MuseumBut she said the project was important and the support they all received from within their group and from Ceredigion Museum’s curator Carrie Canham meant she looked forward to their monthly meet-ups.

“I think that’s why people stayed in the group and why what you get [the artworks] is so powerful,” she said.

The museum said it anticipated that the discussion of topics relating to enslavement and colonialism could be challenging and emotional for the community groups involved and had been reassured by Ceredigion Museum that they had selected a project coordinator who was also of global majority heritage (this term refers to all people who are non-white and make up 80-85% of the global population), with previous experience of working on similar projects.

The Trustees of the British Museum

The Trustees of the British MuseumGroup member Shamira Scott agreed the group had leant on one another.

“We were able to console each other and comfort one another through our words and encourage each other as well. I think that’s what got us through,” she said.

Shamira, who created a film about the project, said her Jamaican grandparents’ grandparents would have been enslaved.

“For us the history is very close,” she said.

“It has been overwhelming… it was a very sad subject for me to engage in.”

She said the artworks produced were “uplifting despite the sadness we have all shared in”.

The Trustees of the British Museum

The Trustees of the British MuseumDéa’s creative response to the collection included two woven circles and she also led on a collective piece from the group – sculptural hands which symbolise the absence of enslaved people’s stories in the Sloane collection, even though they often made the objects or assisted in their collection.

“Collectively it felt like a really clear visual way to bring the presence of those lost voices to life in the museum,” she said.

Like the others, she said she found the whole experience was “really emotional”.

She said projects like this were the “tip of the iceberg” and radical change was needed in the teaching of history in school and greater representation in museums and all institutions.

She wants to see museums “making a greater effort to employ global majority people who are specifically trained in these areas and these topics to be part of projects like this”.

She acknowledged that they had only come into contact with “a small group of people” from the British Museum but said it was still something “we all felt aware of and all noticed”.

The museum said of those who have declared their ethnicity, 18.4% of its workforce was from the global majority, with 9% in senior or decision-making roles.

It said it had two full-time equality, diversity and inclusion managers and was taking steps to improve the diversity of its staff.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOn hearing the thoughts of the Voices from the Edge group, Ceredigion Museum’s curator Carrie Canham said: “I absolutely agree with the group.”

She added: “We’re a small museum, we have seven people who work for this museum and one person works full time out of the service.

“There’s massive capacity issues within the sector because everything has shaved down to the bone really in terms of our service and what we can do so project work like this is really shaped by external funding that’s available.”

She said she would like to see museums becoming a statutory service so that they are publicly funded as well as better representation at museums.

Dr Alicia Hughes, Project Curator for the Sloane Lab at the British Museum, said she had been “blown away” by the very, very thoughtful conversations, time and commitment that each member of the group has given to the project, adding: “it is a very, very complex subject, it’s a very emotional subject and it is something that the museum has a responsibility to address”.

She said the “process of listening to the group and what was important to them has been really powerful for myself”.

Dr Hughes said one of the reasons Ceredigion Museum had been selected for the touring exhibition was because in its application it said it wanted to work with Voices from the Edge and that emotional support would be provided within the group.

“So we understood from the beginning of selecting Ceredigion that that was going to be something that was provided for within the project,” she said.

She said she agreed that more funding should be available for projects like this.

A Welsh government spokesperson confirmed it funded the AIM Re:Collections programme which helps museums deliver the goals of its Anti-Racist Wales Action Plan, which included establishing the Voices from the Edge group.

It said the group’s work was “invaluable in demonstrating how Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic perspectives and experiences need to be treated as a natural part of the histories that museums document and explore”.