Getty Images

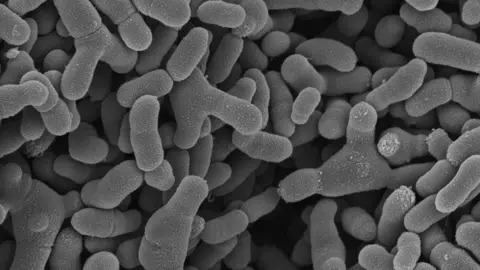

Getty ImagesScientists have studied more than 2,000 samples of poo from babies in the UK to get a clearer idea of which types of bacteria first colonise a newborn’s gut.

Researchers say they were surprised to find baby poo fell into three distinct microbiological profiles, with different “pioneer bacteria” being abundant in each.

One in particular, called B. breve, could help babies make the most of nutrients in breast milk and ward off bugs, preliminary tests suggest.

Another type could be harmful and put babies at greater risk of infection, the early work, published in Nature Microbiology, shows.

There is growing evidence that a person’s microbiome – the ecosystem of millions of different microbes living in our guts – has a wide-ranging influence on our health.

But there are few studies on the make-up of a baby’s microbiome as it develops in the first few days of life.

Scientists from the Wellcome Sanger Institute, University College London and the University of Birmingham studied stool samples from 1,288 healthy infants who were all born in UK hospitals and were under one month old.

They found most samples fell into three broad categories with different bacteria being dominant.

B. breve and B. longum bacteria groups were thought to be beneficial.

Their genetic profiles suggest they can help babies utilise the nutrients in breast milk.

However, E. faecalis could at times put babies at greater risk of infection, preliminary tests show.

Wellcome Sanger Institute

Wellcome Sanger InstituteMost babies in the study were fully or partially breastfed in the first few weeks of life.

But whether the baby had breast milk or formula milk did not seem to influence the type of pioneer bacteria in their gut, researchers say.

Meanwhile, babies of mothers who were given antibiotics in labour were more likely to have E. faecalis present.

It is not yet clear if this has any long-term health impacts.

And other factors such as the mother’s age, ethnicity and how many times someone has given birth, also play a role in the developing microbiome.

More work is being done to determine the exact impact of these microbes have on children’s long-term health.

Dr Yan Shao, from the Wellcome Sanger Institute, said: “By analysing the high-resolution genomic information from over 1,200 babies, we have identified three pioneer bacteria that drive the development of the gut microbiota, allowing us to group them into infant microbiome profiles.

“Being able to see the make-up of these ecosystems and how they differ is the first step in developing effective personalised therapy to help support a healthy microbiome.”

Meanwhile, Dr Ruairi Robertson, Queen Mary University of London lecturer in microbiome science and who was not involved in the research, said: “This study significantly expands on existing knowledge about how the gut microbiome assembles in the first month of life.

“We have gained a lot of knowledge in recent years about the influence of birth mode and breastfeeding on gut microbiome assembly and the implications for common childhood disorders such as asthma and allergies.

“However, this has not yet translated into effective microbiome-targeted therapies.”

Prof Louise Kenny, from the University of Liverpool, said decisions around childbirth and breastfeeding were “complex and personal” and there was no “one-size-fits-all approach” when it came to the best options.

“We still have an incomplete understanding of how the role of mode of birth and different methods of infant feeding influence microbiome development and how this impacts later health,” she said.

“That’s why this research is vital,” she added.

This research is part of the ongoing UK Baby Biome study and is funded by Wellcome and the Wellcome Sanger Institute.

One of the authors, Dr Trevor Lawley, is a the co-founder of a company working on adult probiotics as well as a researcher at the Wellcome Sanger Institute.