BBC

BBC- Biddy Baxter, who transformed Blue Peter and children’s TV, dies aged 92

- She led the show from 1965 to 1988, introducing many of its best-loved features

- Ex-presenters pay tribute to a “force of nature” and discuss her formidable reputation

Long-serving Blue Peter editor Biddy Baxter, who turned the children’s show into a television institution, has died at the age of 92.

During her tenure, which lasted from 1965 to 1988, she introduced generations of children to the pleasures of sticky-backed plastic, on-screen pets, presenters’ adventures and charity appeals – a recipe that stood the test of time.

She was also passionate about getting her viewers involved in the programme, long before audience participation became an industry mantra.

But she also gained a reputation as a formidable figure – a tyrant who fell out with presenters and jealously guarded the Blue Peter brand.

Peter Duncan, who was among the show’s presenters in the 1980s, told BBC Breakfast she was “a wonderful, inspiring person” and “a true force of nature”.

“She was a true enthusiast and a supporter of young people,” he said.

‘Absolute powerhouse’

The presenters could get “a right old telling off” if they messed up, but “I loved working with that kind of energy and that kind of expectation”, Duncan said.

“She was truly a one-off within the BBC. If something upset her, she would trail off to see the DG (director general) and tell him what she thought. We need people like that now more than ever.”

Peter Purves, who starred on the show in the 1960s and 70s, described Baxter as “an absolute powerhouse”.

“She controlled everything about the programme, and with quite a rigid hand,” he told BBC Breakfast.

“We didn’t always get on because of that, but she knew exactly what she wanted the programme to be, and it was a success absolutely because of her. She was a remarkable woman.”

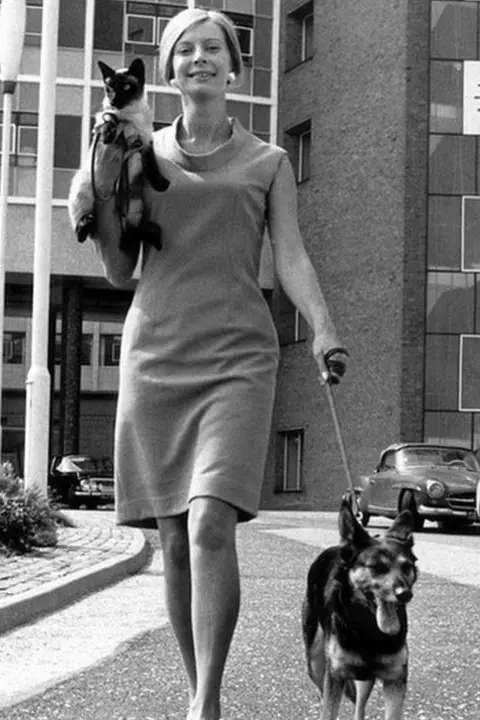

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe BBC’s chief content officer, Kate Phillips, paid tribute to Baxter as “a truly inspirational television producer who transformed children’s broadcasting through her passion and commitment”.

“I was fortunate enough to work with Biddy, she was fabulous, formidable, and visionary, ensuring that children’s thoughts, interests and ideas were at the very heart of Blue Peter,” she said. “She enriched the lives of millions across the country and leaves an enduring legacy.”

Another former presenter, Janet Ellis, told BBC News that Baxter was “an extraordinarily gifted woman” whose approach was “one of a kind”.

She said: “I think a lot of the adjectives applied to Biddy are because she was a woman – particularly at the time when she started working, when there weren’t that many women in senior positions.

“So, all the stuff like ‘formidable’ and ‘one track’ and everything I don’t think would necessarily be applied to a man of her generation.”

Joan Maureen Baxter was born in Leicester in May 1933. There were too many Joans in her class at school, so a nickname was made up on the spot.

Her upbringing during World War Two instilled in Biddy an ability to make do and mend, which later became part of the Blue Peter ethos.

“My friends and I held bring-and-buy sales for the Spitfire fund and put on plays and concerts for the British Red Cross and Aid to France,” she said.

She was educated at a local grammar school before going to St Mary’s College, Durham University in 1952. At that time, only 6% of undergraduates were women.

The experience shaped the rest of her life. “For three memorable years, Durham was my life.”

Baxter had intended to become a prison officer or a social worker. But, by chance, she noticed the BBC was advertising for staff.

She turned down suggestions from a university careers officer that women were best suited to teaching or secretarial work.

“He said to me, ‘No-one from Durham has ever worked for the BBC,’ so I applied. I really should be grateful to him.”

She joined the BBC in 1955 as a radio trainee studio manager, creating sound effects. She was promoted to producing Schools Junior English programmes and Listen with Mother in 1958.

She had a brief spell in children’s television to cover a period of illness and applied for a permanent job soon after. One radio colleague branded her a traitor for defecting to television.

In 1962, she was asked to take over as producer of Blue Peter, a programme whose life expectancy was thought to be short.

Conceived as something for children who had outgrown Watch with Mother, its survival was resting on the fact it was cheap to make.

The programmes, which lasted 15 minutes, were presented by Christopher Trace and a former Miss Great Britain, Leila Williams.

‘Fur more important than flesh’

Williams was fired just before Baxter joined the programme, and a new presenter, Valerie Singleton, was recruited to work with Trace.

Baxter tore into the programme like a whirlwind. Within a year she had introduced the iconic Blue Peter badge after commissioning a young artist called Tony Hart to design the ship logo.

She also decided to recruit a dog, so viewers who did not have a pet could share in a sense of ownership.

Unfortunately, the animal died just two days after its first appearance at Christmas 1962. Baxter and her producer, Edward Barnes, decided not to inform the viewers but instead substituted a sad-looking mongrel they discovered in a south London pet shop.

The audience, innocent of the switch, were asked to come up with a name for the puppy. They chose Petra.

Two years later, when children were asked to write in for a photo of the dog, more than 60,000 applied.

When Petra died in 1977, there were newspaper obituaries worthy of a film star.

“Fur and feather are more important than flesh,” Baxter used to tell presenters.

It was reported that she once threw her handbag at a director who failed to get a close up of Goldie, the programme’s golden retriever.

Baxter was appointed the programme’s editor in 1965 and the transformation of Blue Peter continued.

Location filming was introduced, more pets appeared, and appeals were launched to collect old toys and silver paper for good causes.

It was early example of recycling and designed so that even the poorest viewers could take part.

Baxter’s stroke of genius was to tap the resources of her viewers by asking them to contribute ideas for things they wanted to see in the programme.

The letters poured in, and Baxter set up a complicated card index system so children would get personal replies rather than a formatted letter.

“We could check the index and reply, ‘Last time you wrote, your hamster had a sore paw. I do hope it’s better.’ It’s only a tiny thing, but children aren’t stupid.”

Baxter later estimated that 75% of the show’s content was based on ideas submitted by its audience.

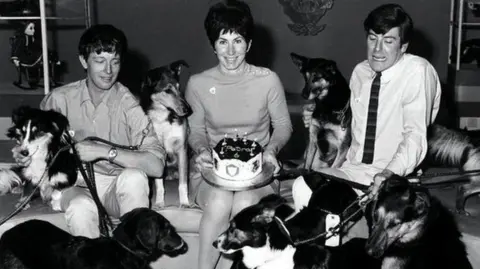

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWith ratings improving, Blue Peter was now on twice a week.

Baxter fought hard for the programme, insisting on the best studios and resources.

She found a piece of waste ground behind Television Centre and created a garden.

Stiletto heels

Baxter abolished gender stereotyping before the phrase was invented. Male presenters were expected to take their share of cooking duties.

But while the presenters were the public face of Blue Peter, there was never any doubt about who ran the show, and most of her team were in awe of her.

One studio manager recalled that her habit of striding across the studio in stiletto heels damaged the floor, but no-one had the courage to tell her.

Baxter firmly believed no presenter was bigger than the programme, and gave short shrift to any of them who she felt had fallen below the standards she expected.

“They can always go and work somewhere else,” she once exclaimed.

Singleton once complained she treated presenters like children. John Noakes called her awful: “She was a bully who treated me like some country yokel from Yorkshire. I couldn’t abide her.”

Yvette Fielding, who joined in 1987, characterised Baxter as “incredibly cruel”.

One former producer was once asked whether there was a hierarchy. “Yes,” he replied. “There was Biddy at the top and everyone else at the bottom.”

Baxter herself said she “never thought of me as being the slightest bit frightening”.

But the “golden rule” was that the audience came first, she said. “We had to all give it our best possible shots and you never do get perfection. You never come to the end of a programme and think, gosh that was good. Always, always, something goes wrong, but it doesn’t mean you should stop trying.”

In the 1980s, Blue Peter was looking decidedly old-fashioned against brash newcomers to children’s TV like ATV’s Tiswas.

Childhood was changing and it was decidedly uncool to admit to watching the programme.

It also came under attack from commentators who bemoaned its lack of diversity and claimed it peddled middle-class values.

“All these people who witter on,” exclaimed Baxter. “The bottom line is, do people want to watch it? They did and do in their millions. Therefore I do not believe it’s smug, self-satisfied and class-ridden.”

Baxter left the programme in 1988. There are different stories about her departure.

At the time, it was reported that she decided to leave when her husband, the musicologist John Hosier, was offered a job in China and she decided to go with him.

But Richard Marson – her colleague-turned-biographer – insisted she was “manoeuvred out in the summer of 1988 by a new head of children’s programmes who wanted the show to evolve without its all-powerful matriarch”.

She was devastated, but did not complain in public.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOn her departure she was awarded a Blue Peter Gold Badge, the programme’s highest honour. She worked as a freelance consultant to various BBC directors general until her retirement in 2000.

In 2013, she was given a special Bafta award. One former BBC chief told the Guardian at the time: “Somehow she was overlooked. If anyone deserves to be recognised she does.

“Blue Peter is a legend and she is Blue Peter.”

BBC News used AI to help write the summary at the top of this article. It was edited by BBC journalists. Find out more.