The second in an occasional series of profiles on Southern California athletes who have flourished in their post-playing careers.

The expansion Los Angeles Angels were just 5 months old in September 1961 when the team called up three minor leaguers who would come to define the fledgling franchise’s early years.

Jim Fregosi, a teenage shortstop, would go on to make six All-Star teams and win a Gold Glove. Right-hander Dean Chance, who turned 20 that summer, would win Rookie of the Year and Cy Young awards and lead the American League in wins, ERA, shutouts and innings pitched. And Buck Rodgers would catch for nine big league seasons before managing at the minor and major league level for the Angels.

But only Dan Ardell, a light-hitting first baseman who was called up with them, would do something that had never been done before on Sept. 20 against the Detroit Tigers. In his first big league plate appearance, Ardell blooped a single to right field, only to see pinch-runner Ken McBride get caught rounding second base to end the game.

“I’m the only one to only get one hit. And the one hit was a walk-off loss,” he said. “Not easy to do.”

There were few witnesses since many in the crowd of 3,116 at Detroit’s Tiger Stadium had left long before the ninth inning. Ardell would appear in six more games, four as a pinch-runner, and make six more plate appearances without a hit, striking out twice, walking once and dropping down a sacrifice bunt to finish with a .250 lifetime batting average.

It wasn’t good enough to get him a plaque in the Hall of Fame but you can still find him listed there, alongside the other 20,964 men who have played in the majors.

“It’s a very low number,” Ardell said, acknowledging the accomplishment. “Very low.”

Yet more than six decades later, Ardell looks back on his month with the Angels with neither delight nor disappointment. He has gone on to live a rich life, one that has included well-paying jobs in banking and asset management, a 41-year marriage that produced four children and six grandchildren, and absolutely no regrets about a baseball career that was so short it’s remembered mostly for a teammate’s base-running blunder.

1. Jim Fregosi during a game in Anaheim in 1965. (Transcendental Graphics / Getty Images) 2. Dean Chance won a Cy Young Award with the Angels. (Associated Press) 3. Rich Rollins of the Minnesota Twins swings and misses as Angels catcher Buck Rodgers catches the pitch in a 1962 game. All three players were called up to the Angels in September 1961 along with Dan Ardell, whose career only lasted seven games. (Hy Peskin Archive / Getty Images)

“I never had a desire to be a major league ballplayer,” said Ardell, a retired real estate executive who made $1,250 for his big league cameo. “I loved playing baseball, but once I started playing professionally, I was bored. I was disinterested.”

In fact, the bookish Ardell probably never should have been there at all. But after winning the College World Series as a sophomore at USC, he accepted a $37,500 bonus to leave school five semesters short of a degree to sign with the Angels.

Still, he hedged his bets just the same.

“They wanted to give me $35,000 and I said I need $37,500 because that would give me the $500 a semester [tuition] at ‘SC that I needed,” Ardell said.

The newly born Angels had just two minor league teams, so Ardell was sent to the Dodgers’ Class D farm club in Artesia, N.M. His manager was Spider Jorgensen, whose big league debut in 1947 had been somewhat overshadowed by teammate Jackie Robinson, who broke baseball’s color line that day. Since Jorgensen’s equipment never made it to the ballpark, he played third base that day using an infielder’s glove he borrowed from Robinson.

The team Jorgensen managed went 48-78 and finished last, 29½ games out of first in the Sophomore League — so bad that Sports Illustrated came to New Mexico to document its mediocrity. Ardell finished that first season with more strikeouts (32) than hits (30) in 125 at-bats, but he was big, left-handed and played first base — three attributes that were enough to get him a trial with an Angels team that entered September 30 games behind the league-leading Yankees.

“I basically played second string at ‘SC,” Ardell said. “So I go from second string to Class D ball — which wasn’t as good as our ‘SC team — to the big leagues all within 60 days. At age 20, it was an incredible roller coaster.”

It was a ride he quickly tired off. He didn’t drink and he was about to get married, so the frat house atmosphere of a professional baseball team wasn’t one he partook of. After three more minor league seasons, he retired at 23.

“I learned a lot about myself,” he said of those three mostly unhappy summers.

It wasn’t that he couldn’t do it. It was that he didn’t want to do it. Being a big league ballplayer may have been some kids’ dream, but it wasn’t his.

“I got no satisfaction out of it. And I was bored,” he said. “It just wasn’t that interesting to me once I had to make my living doing it.

“If you don’t love what you’re doing, if you don’t appreciate and like what you’re doing, it becomes hard work.”

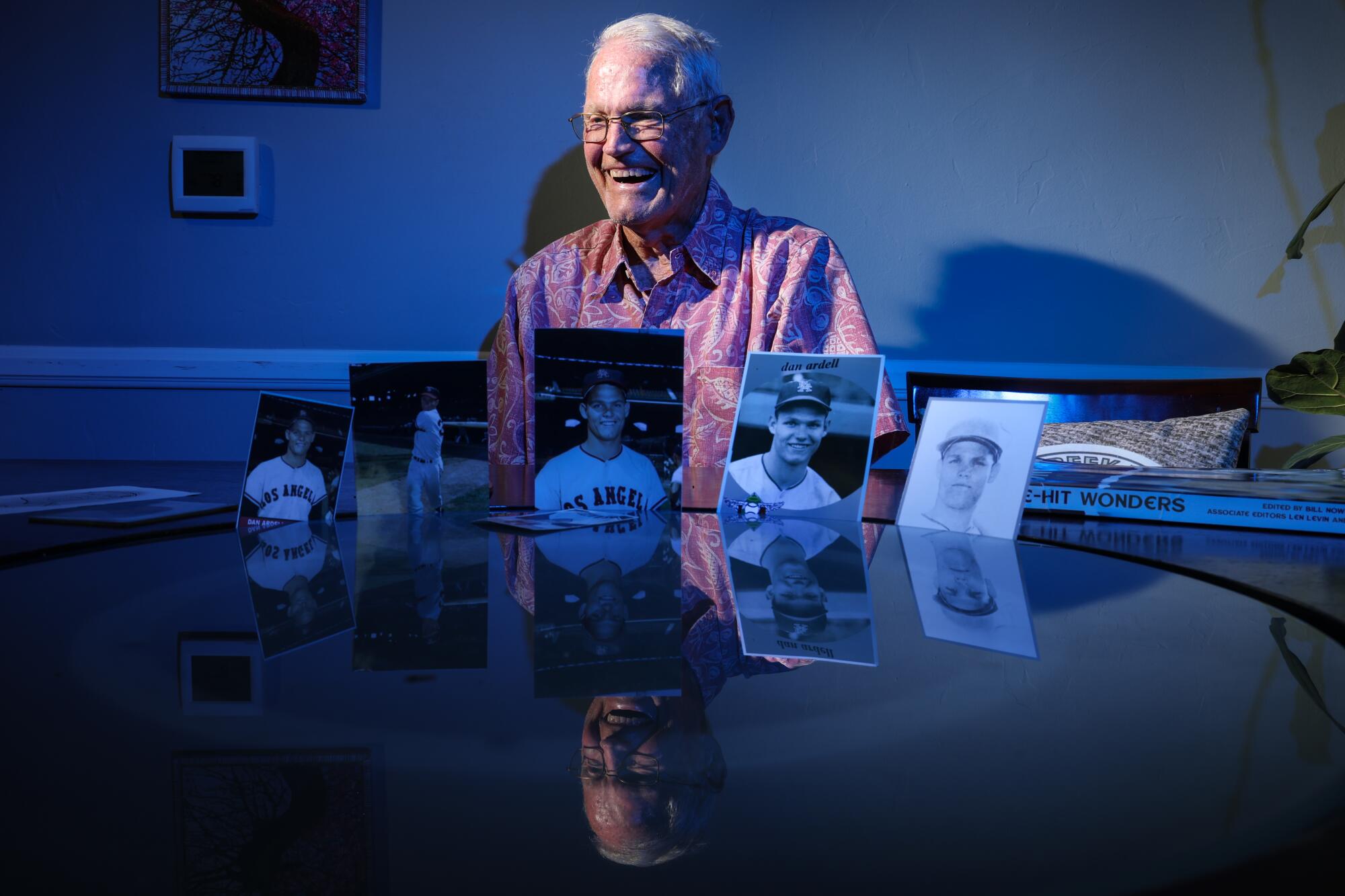

At 84, Ardell has an easy smile and a quick, self-deprecating wit he employs often. He’s still at his playing weight of 190 pounds, but he says he’s lost 2 inches off a frame that once rose to 6-foot-2. And he no longer moves with the speed or grace that allowed him to steal seven bases in his first minor league season.

There is no memorabilia, no remnants of his short-lived career in his hillside home in Laguna Beach’s Bluebird Canyon, about a half-mile from the Pacific Ocean. He gave his gloves away during a garage sale shortly after he quit playing and a grandson took down the few pictures he had hung on the wall.

After retiring with a .252 average and 45 home runs in 389 minor league games, Ardell went back to college, then studied real estate, working for Union Bank and Wells Fargo. He eventually started a real estate asset management company with his twin brother Dave, an equally talented baseball player who played at UCLA, where he was the team captain.

After retiring with a .252 average and 45 home runs in 389 minor league games, Dan Ardell returned to school at USC, then studied real estate, working for Union Bank and Wells Fargo.

(Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times)

That anyone remembers he played at all is both flattering and befuddling for Ardell, who receives about a dozen autograph requests in the mail each year.

“I mean, how do they even know my address?” he asked.

Still, he answers every letter. Some fans send old photos or baseball cards that are necessarily homemade since Ardell never got a Topps bubblegum card of his own.

“In those days anybody who signed a bonus, Topps would sign,” he said. “So they came to Artesia, where I was playing, and said ‘we want to give you a Topps card. And we’ll pay you five bucks’.

“I said, ‘I think I need 10.’ So I’m the only only major leaguer who never had a Topps card.”

Which isn’t to say Ardell has no mementos from his career. A fastball he didn’t see on a poorly lit field in San José slipped under the bill of his batting helmet and struck him flush in the head one night.

“I woke up the next day. You could see the seam where the baseball hit. I still have a dent,” he said with a chuckle, pointing to a spot in the center of his forehead.

It wasn’t until three decades after he walked away from the game that Ardell came to appreciate what he had accomplished — and only then after marrying Jean Hastings, who would shortly become a nationally recognized baseball academic and writer.

Ardell and Hastings — a Brooklyn native who had always been a baseball fanatic — were living in the same Orange County neighborhood when a mutual friend suggested they go out on a date.

“She had just read ‘Ball Four,’” Ardell said, referencing Jim Bouton’s book about the raunchy, less-seemly side of baseball. “So she said no, baseball players are to look at, they’re not to touch.”

Dan Ardell says he receives about a dozen autograph requests in the mail each year, with some fans sending old photos or homemade baseball cards since Ardell never got a Topps card of his own. “I mean, how do they even know my address?” he said.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

She went on the date anyway, then married Ardell a couple of years later in 1981. Jean, 79, died in 2022 after a short, ferocious battle with leukemia, but in the more than 40 years she spent with Ardell, she slowly rekindled his love for a game he had all but forgotten.

They went to conferences and symposiums, where Jean spoke on the magic and the poetry of baseball. They visited the Hall of Fame, traveled to Arizona for spring training and attended countless Angels games, watching on TV the ones they couldn’t attend in person.

“It was definitely part of her,” grandson Garrett Tyler said.

Jean not only helped Ardell put his baseball career into perspective, she helped put his life in perspective. Shortly after they married, “I decided to have a mission statement,” Ardell said. “And my mission statement was to make a difference in the lives of others.”

“Ten years later,” he added “I changed it to make a positive difference.”

He saw that desire at work in Jean, a political liberal who, in addition to her baseball writing, also worked with a nonprofit called Braver Angels that seeks to bridge the political divide by bringing Democrats and Republicans together. It was a philosophy she lived by marrying Ardell, a lifelong Republican who cast his first presidential vote for Barry Goldwater but later drove a car sporting a “Republicans for Obama” bumper sticker.

Ardell was already working with Opportunity International, a global nonprofit that alleviates generational poverty by microfinancing community projects both in Southern California and abroad. But now the bridge that he and Jean built became apparent through the difference being made — not only in those affected communities, but in his own soul as well.

Tyler said he grew up playing catch with his grandfather, who attended all his Little League games. But it was his grandmother who told him about Ardell’s professional career.

“He was always a little bit reluctant to talk about it. My grandma was the one that kind of opened him up,” said Tyler, 25, who followed his grandparents into baseball, where he works as manager of concessions for the Amarillo Sod Poodles, the double A affiliate of the Arizona Diamondbacks.

“I’ve talked to him a lot about that. He told me that he just didn’t have the confidence. He knew that he was good, but I don’t think he really understood it. I don’t know if he necessarily misses it or feels like he missed out. I think he was more appreciative of the journey that it took him on and how he’s evolved into a different love for baseball.”

As he has grown older, Tyler said that’s the part of his grandfather’s journey that has stuck with him; the mission statement part that says it’s not about the destination or the accomplishments, but about the influence you have on those you meet along the way.

In that way, he said, Ardell’s short career is now having an outsized influence.

Tyler mentions a friend who is basically playing for free, stranded below the longest rung of the minor league ladder. But he still puts on a uniform every day.

“He plays for the love of the game and just because it’s all he knows,” Tyler said. “One of the things that Dan asks me that I ask my friend is, ‘do you like what you’re doing?’ And at that point it’s not about your career longevity or how much money you’re making.

“As long as you’re happy playing and you’re making ends meet, then go for it.”

Ardell wasn’t happy playing, so he walked away. Three decades later with the love and support of a wife who saw baseball not as a sport but as a metaphor for life, as a game where the goal is to get home safely, Ardell began to understand the magic, too.

His one month in the majors led him to a career prosperous enough that he could help others, one that still fills his mailbox with letters from fans and one that has given him the wisdom to counsel other 23-year-olds to keep putting on the uniform as long as it fits.

Make a positive difference in the lives of others.

“It was a very inconsequential part of my life that was very consequential to other people,” Ardell said of his one month in the majors.

“I think of it every day.”