On the darkest night of their season last week, the Dodgers didn’t linger in their hushed home clubhouse.

The team had just been blown out in Game 2 of the National League Division Series. They’d lost their cool (and watched their home crowd do the same) in a 10-2 rout to the San Diego Padres. But rather than dwell on the disaster, they quickly packed team-branded duffel bags and boarded a charter bus waiting out in the parking lot.

With their season on the line, they were headed to San Diego.

And, this time, they decided as a team to all travel together.

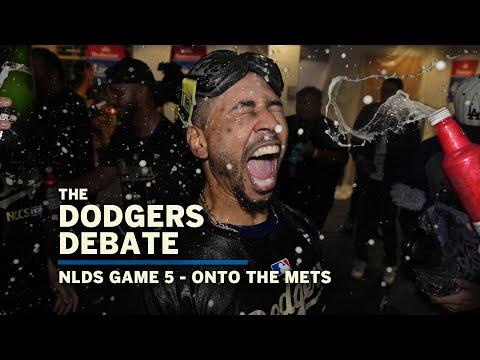

Dodgers Max Muncy and Kiké Hernández celebrate after the team beat the Padres and won the NLDS series on Friday at Dodger Stadium.

(Gina Ferazzi/Los Angeles Times)

“For as long as I’ve been here, we’ve never taken a team bus to San Diego, ever,” veteran third baseman Max Muncy said. “And that’s not a bad thing by any means. But us saying, ‘We’re all gonna ride a bus down there, no families, nothing else, just us on a bus,’ It was great.”

And as the Dodgers prepared to open their NL Championship Series against the New York Mets on Sunday, it served as one of the many little examples that ultimately helped them advance.

Entering the playoffs, the Dodgers tried to be different in their postseason process, with a player-driven emphasis on cliche traits like togetherness and team unity generating a more resilient, combative mindset.

During the past few seasons, the Dodgers have lacked such ingredients once they’ve reached October. In NLDS eliminations in 2022 and 2023, their inability to conjure a heightened level of intensity seemingly contributed to stunningly early exits.

“We haven’t had that edge,” Muncy said. “We haven’t had that attitude.”

So, as they embarked on a third-straight postseason that began with an awkward first-round bye week, players brainstormed ways to avoid that pitfall again.

The process started during the final week of the regular season, when Muncy, catcher Will Smith and shortstop Miguel Rojas concocted a plan to hold team watch parties at Dodger Stadium during the wild-card round; aiming to not only scout potential NLDS opponents as a group, but also spend more of their week off in one another’s presence.

“I think just talking with some of the other guys, the leaders, it was, ‘How can we stay in a rhythm?’ ” Smith said. “It’s hard to come out of a rhythm in baseball. We’re playing every day and all of a sudden we get a week off. So how can we stay in rhythm? Be at the field for a decent amount of time like we do in the season.”

It also bled into the way the Dodgers handled their team workouts during the five-day break, with players agreeing to stay at the ballpark until the end of each session.

“I think a lot of guys maybe got a little bit complacent with the bye week the last couple years,” Hudson said, using the word “informal” to describe the mood of their 2022 and 2023 preparation. “We came in this year and tried to make sure we didn’t do that again.”

Ideas for change, Muncy said, not only originated in the clubhouse, but were presented by players to front-office officials.

“What we did for the five days off, everything was constructed by the players,” Muncy said. “Instead of us saying, ‘What does the organization want us to do? What are we going to do for that?’ It was the players saying, ‘No, this is what we’re doing. This is how we’re going to do things as a team.’ That’s been 100% player-driven.”

The bus ride to San Diego became another prime example.

Typically, when the Dodgers head south for road games against the Padres, most players drive down Interstate 5 themselves with their families. While the team does offer a bus for those wary of battling traffic, “not a lot of people take it,” Kiké Hernández said.

But, in a postseason all about doing things differently, even something as small as a more unified travel schedule proved to have profound team-wide effects.

Rather than stew on the Game 2 loss individually, the Dodgers’ ride last week transformed into “a party bus for two hours,” Hernández recalled with a laugh.

Dodgers third baseman Max Muncy (13) celebrates on second base after hitting a third inning double in Game 4 of the NLDS at Petco Park.

(Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times)

“Especially,” he added, “when the driver is hauling ass and we make it to San Diego in an hour, 40 [minutes].”

To Muncy, it became something of a turning point in the series.

“We needed that,” he said, “to help us get over that shellacking we took in Game 2.”

The Dodgers didn’t win Game 3, but their near-comeback from an early five-run deficit showcased some fight they’d been missing in the past.

Before Game 4, their new approach was summed up in a blunt rallying cry delivered by Hernández.

“F— them all,” the 33-year-old repeatedly told his teammates.

“That’s the attitude we’ve had here,” Muncy added. “It’s just kind of who we’ve been this year.”

Two shutout wins later, the Dodgers clinched their first NLCS appearance since 2021. And as the team celebrated with a Champagne shower in the clubhouse, their internally stoked fire was evident in a string of expletive-filled answers.

“We have a lot of ‘F U’ in us,” Hernández said. “We’re all here together for one reason and one thing and one thing only. And that’s to win the World Series.”

To do that, the Dodgers will need to keep those flames burning in their series against the Mets.

Unlike the NLDS, when the Padres were the popular pick among online and television pundits, the Dodgers are now the consensus — or, at least, betting — favorites to win the league championship series and advance to the Fall Classic.

In past years, it’s the kind of situation in which they’ve failed to meet the moment. This time, however, they’re hoping their newfound edge can combat a similar collapse.

“We remember the last two early exits,” Hudson said. “And we want to put that behind us.”

“Usually, when people are in it together,” Hernández added, “good things tend to happen.”