BBC

BBCSuddenly, Malak stops speaking, leans forward a fraction and kisses the baby sitting on her lap. Her sister Rahma is fair-haired and has blue eyes. There is a 13-year age difference between them. But to Malak – who lost her father in an Israeli attack – the four-month-old baby is an unimaginably precious gift.

“I love her so much, in a way no-one else knows,” she says.

The BBC went back to meet Malak and others in Gaza as the first anniversary of the war approached. We first interviewed Malak in February, just after the death of her father, Abed-Alrahman al-Najjar, a 32-year-old farm labourer.

The father of seven, believed to have been hit by shrapnel, was among more than 70 people killed during an Israeli commando operation to rescue two hostages held by Hamas in Rafah. He was asleep with his family in a refugee tent when the raid happened.

Their tent was close to the scene of the fighting. Malak lost an eye in the attack. She also suffered a wound in her side. Back then she was severely traumatised – when she met a BBC colleague, she called out in anguish, “I am in pain. I lost my dad. Enough!”

Since then, doctors have fitted a small white sphere in her empty eye socket. It will have to suffice until the war ends and she hopefully can be fitted with a proper prosthetic eye.

But Malak does not complain about this loss – rather, she imagines how her father would react if he could hold baby Rahma, born three months after his death. She smiles and says: “He always wanted to have a daughter with blue eyes.”

After what has happened, Malak wants to train as an eye doctor, to help others who suffer as she does.

She is sitting on a concrete floor in Khan Younis in southern Gaza with the baby and her five other younger siblings – three sisters, two brothers, aged between four and 12 years old. Before the war, their father worked hard on other people’s farms to support his family.

“Our father used to take us out and buy us clothes in the winter. He was so kind to us. He would deny himself but never us,” Malak remembers.

Then came 7 October 2023, and the Hamas assault on Israel in which over 1,200 Israelis were killed – among them, dozens of children. More than 250 hostages were abducted into Gaza. There were 30 children seized, including a baby of nine months.

The attack triggered Israel’s ground invasion, relentless air strikes and fighting with Hamas. Almost 42,000 people have now been killed, according to the Hamas-run health ministry. About 90% of Gaza’s population – nearly two million people – are displaced, according to the United Nations. Malak’s family has been uprooted four times.

“I carry a pain that even mountains cannot bear,” she says. “We were displaced, and it feels like our whole life is displacement. We move from place to place.”

The Israeli government refuses to allow foreign reporters into Gaza, and the BBC relies on a team of local journalists to cover the humanitarian crisis. We briefed them with questions and asked them to contact some of the Palestinians we have spoken to in Gaza over the past 12 months.

These journalists share the fear and displacement of the people they report on. Displacement means uncertainty. Constant fear. Will the child, sent for a bucket of water, come home? Or will they return to find their home flattened, and their family buried under the rubble? These are the questions that haunt Abed-Alrahman’s young widow, Nawara, every day.

“There is always shelling and we are always afraid, terrified. I constantly hold my children close and hug them,” she says.

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) tell people to move to so-called “humanitarian zones”. People flee but often find no safety. When they move, the struggle to locate food, firewood and medicine in an unfamiliar place starts again.

The al-Najjars are now back in their family home, but they know they may have to flee again. That is the inescapable reality of their lives after a year of war. In the words of Nawara, there is “no safe place in the Gaza Strip”.

Nawara complains of the overflowing sewage in the street. The lack of medical supplies. Like so many in Gaza, with no income, she depends on what food her in-laws or charities can supply.

There are no schools open for her children, who are among the 465,000 that Unicef – the UN Children’s Fund – estimate are affected by school closures there.

“Our health – my children’s and mine – is bad. They are always sick, always have fevers or diarrhoea. They are always feeling unwell,” Nawara adds.

Through all of this, she holds on to the memory of her husband Abed-Alrahman.

“I look at his picture, and keep talking to him. I imagine he’s still alive,” she says. “I keep talking to him on the phone as if he’s replying to me, and I imagine answering back. Every day I sit by myself, bring up his name, talk to him, and cry. I feel like he’s aware of everything I’m going through.”

And Malak too has her daily ritual. She and one of her sisters try to do a charitable deed each day in memory of their father. When possible, their aunt makes a gift of food for the dead man. “At night, we put it out and pray for him,” Malak says.

The stories of Nawara al-Najjar and Malak are a fragmentary glimpse into the suffering of the last 12 months. As the war enters its second year, our BBC colleagues on the ground continue to report on death and displacement. In northern Gaza we re-visited the family of a disabled man who died after being attacked in an Israeli search operation.

___

‘This scene I will never forget’

Muhammed Bhar was terrified. The dog growled and lunged. It was biting, drawing blood and he could not stop it. Around him, the sitting room was full of noise – his mother and little niece screaming, the Israeli soldiers shouting orders.

Muhammed, aged 24, had Down’s syndrome and was autistic – he could not have understood what was happening. When a BBC colleague first spoke to his family in July, they were still struggling with the shock of what had happened.

Muhammed’s mother, Nabila, 70, described what she remembered: “I constantly see the dog tearing at him and his hand, and the blood pouring from his hand.

“This scene I will never forget – it stays in front of my eyes the whole time, it never leaves me at all. We couldn’t save him, neither from them, nor from the dog.”

Handout

HandoutThe incident happened on 3 July, as troops were engaged in intense close-quarter combat in Shejaiya. The IDF said that there were “significant exchanges of fire between [its troops] and Hamas terrorists”.

According to the IDF, troops were searching buildings for Hamas using a dog – these animals are regularly used to hunt for fighters, booby traps, explosives and weapons.

“Inside one of the buildings,” the IDF said, “the canine detected terrorists and bit an individual.” The soldiers restrained the animal and gave Muhammed some “initial medical treatment” in another room.

Nabila Bhar said a military doctor arrived and went into the room where Muhammed was lying. His niece, Janna Bhar, 11, remembered troops saying he was “fine”.

Two of Muhammed’s brothers were arrested during the raid, according to the family. They say one has since been released.

Nabila said the rest of the family was ordered to leave. They pleaded to be allowed to stay with the wounded Muhammed. The IDF said they were “urged to leave to avoid staying in the combat area”.

Some time after this – the army has not said how long – the troops left. The IDF said they went to help soldiers who had been ambushed. The army report for 3 July named Capt Roy Miller, 21, as having been killed, and three other soldiers wounded, during fighting in Shejaiya.

Muhammed was now alone. The IDF statement did not say what condition he was in when the soldiers left. His brother Jibreel believes he had not been given proper treatment.

“They could have treated him much better than they did, but they just put some gauze on him, as if they did a quick, careless job. Whether he lived or died didn’t seem to matter to them,” he says.

The Israelis withdrew from the neighbourhood a week later and Muhammed’s family returned. They found him dead on the kitchen floor.

It is still not known what exactly caused his death after he was attacked by the dog. In the current wartime circumstances the family has not been able to have an autopsy carried out.

The young man was buried in an alleyway beside the house because it was too dangerous to go to the cemetery where his father – who died before the war – was interred.

Three months later, Muhammed is still interred in the alleyway. His brother Jibreel has covered the grave with plastic sheeting, some concrete blocks and a sheet of corrugated iron. It is surrounded by a mess of rubble and pieces of metal, the detritus from bombed-out buildings nearby.

Inside, Muhammed’s bedroom has been left shuttered. Jibreel opens the door, walks into the darkness, opens a wardrobe and takes out some of his brother’s clothes. Along with some photographs and family videos, they are the remaining mementoes of his life in the house.

“His personal room was where he exercised, played, and ate, and no-one entered this room except for him,” he says. In the sitting room, Jibreel points to the couch where Muhammed was sitting when the dog attacked. The blood stains have dried into the fabric.

“Every corner of this house reminds us of Muhammad,” Jibreel says. “This is the spot where he would always sit. We would sit around him, making sure not to disturb him. He loved peace and quiet.”

The family wants an independent investigation into his death.

“Once the war ends and international human rights organisations and legal groups return,” says Jibreel, “we will definitely file a legal case against the Israeli army.

“Muhammad was a special case – he wasn’t a fighter, he wasn’t armed, just an ordinary civilian. He wasn’t even just any civilian, he had special needs.”

___

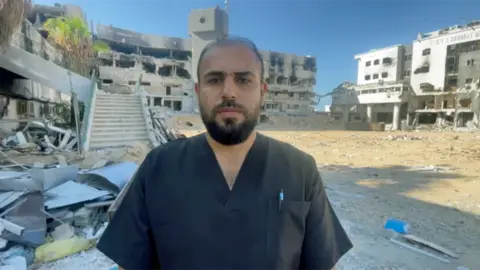

‘The hospital is largely destroyed’

Most of Dr Amjad Elawa’s neighbours and friends have gone. They are either dead or have fled south, hoping it will be safer there. When he walks home from the hospital, he sees people on the streets talking to themselves.

“No one is in their right mind anymore,” he says.

Dr Elawa, 32, works in the Emergency Services department of al-Shifa hospital in northern Gaza. Back at the start of the war it was the largest medical complex in the Gaza Strip. Now, much of the hospital is in ruins following two major raids by the IDF, who said Hamas and other gunmen used the facility to plan and launch attacks in breach of international law. The charge is rejected by Gaza’s health ministry, which accuses Israel of committing war crimes at al-Shifa.

Dr Elawa has seen children die in front of him. Victims of war wounds. Of disease, often caused by the lack of clean water. And when the BBC first met him, the area was facing acute malnutrition.

In February – when the BBC first interviewed Dr Elawa – he described witnessing the death of two-month-old Mahmoud Fatou. The baby boy died soon after being brought to the hospital.

“This child could not be provided with milk. His mum was not provided with food to be able to breastfeed him,” said Dr Elawa. “He had symptoms of severe dehydration, and he was taking his last breaths when he came.”

Dr Elawa’s own son was born 12 days after the 7 October attacks. After the death of Mahmoud Fatou, he reflected on his own family situation.

“We were all shocked – this child could be our child. Maybe my son after a few days will be just like him,” he said. Thankfully, Dr Elawa’s son is healthy and about to celebrate his first birthday.

The doctor faces the same problems as almost everybody else in northern Gaza. His house was destroyed and he had to move with his family to a patient’s home.

The UN and humanitarian NGOs in Gaza say Israel has regularly blocked aid from entering. For example, in the first two weeks of January (the month before we met Dr Elawa), the UN said 69% of requests to move aid and 95% of missions to provide fuel and medicines to water reservoirs, water wells and health facilities in northern Gaza, were refused. Israel denies blocking aid.

Dr Elawa queued for food whenever he could get any free time. This led to him being wounded when Israeli forces opened fire at Nabulsi roundabout in northern Gaza on 29 February.

Thousands of people had gathered, hoping to be given flour from an aid convoy escorted by the IDF. More than 100 people were killed and over 700 wounded according to the Hamas-run health ministry. The IDF said most of the casualties were caused by a stampede as people rushed the trucks.

The army said there were two incidents at the roundabout. It fired warning shots and then shot at individuals who the troops believed were a threat. Numerous survivors challenge that account, and say the stampede was caused by the army firing into the crowd.

Dr Elawa treated his own wound and then went to help survivors. Within days he was back on duty at al-Shifa.

A BBC colleague returned recently to find Dr Elawa still working in the emergency section. He returns to the theme of the wounded children he treats.

“They are the only ones who really stir our emotions, especially when their limbs are lost. It’s a truly emotional and heartbreaking situation. We see children who haven’t experienced much of life yet, losing their legs.”

On a break, he goes outside and points to the ruins of different buildings. “It used to have an intensive care unit, an operating room, and a cardiology department,” he says.

“Whether it’s medical devices, equipment, or anything else, all are completely destroyed, even the beds. We need a fully-equipped hospital, built from scratch.”

When Dr Elawa returned after the second Israeli raid there was an overpowering stench of death from several mass graves. One of the hospital directors, Mohamed Mughir, says there were “signs of field executions, binding marks, gunshot wounds to the head and torture marks on the limbs” of some of the corpses.

The IDF deny allegations of war crimes and say the graves contain bodies exhumed and then re-buried by the army when searching for dead Israeli hostages.

“The claim that the IDF buried Palestinian bodies is baseless and unfounded,” it says.

The UN Human Rights Director, Volker Turk, says that, given what he calls “the prevailing climate of impunity”, there should be an independent international investigation.

There is more food now. Dr Elawa has a supply of flour but says there are no vegetables, fruit or meat. They use canned foods instead.

Like so many who work to save lives in Gaza, Dr Elawa prays for the war to end.

“We want to return to our old lives, to be able to sleep safely, to walk in the streets safely, to visit our loved ones and relatives – those who are still alive.”

Additional reporting by Haneen Abdeen, Alice Doyard and Nik Millard.