YARMOUK, Syria — On a ferociously hot summer morning, the inspectors stepped gingerly through an alley and cast a critical eye at the war-withered buildings in this sprawling Palestinian refugee camp on the edge of Damascus.

The alley was typical of what Yarmouk had become after 14 years of Syria’s grinding civil war, which had cut the camp’s population from 1.2 million people — 160,000 of them Palestinian refugees — to fewer than several hundred and turned what had been the de facto capital of the Palestinian diaspora and resistance movements into a wasteland.

The ramshackle structures that survive — often with missing roofs and walls, and stairs leading nowhere — have little in common, save for their shambolic, ad hoc construction designed less for permanence than speed and low price. Most have a sprinkling of holes picked out by bullets or shrapnel.

“Nothing to repair here. This one we have to remove completely,” said one of the inspectors, Mohammad Ali, his eyes on a pile of indeterminate gray rubble with an orphaned staircase coming out of its side.

He pressed a tablet to record his assessment and sighed as his partner, Jaber Al-Khatib, hoisted himself up on a wall and examined the skeletal remains of a bombed-out, three-story building.

1. A mother and her child walk down one of the destroyed streets in Yarmouk, the once vibrant Palestinian camp outside Damascus. 2. A pile of rubble reflects the damage to the Yarmouk headquarters of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – General Command.

“The columns seem OK,” Al-Khatib called out.

Ali raised the iPad and snapped a picture he would later upload to a central database. It was a bit after 9 a.m. and the heat was already creeping past 96 degrees. And they still had plenty of buildings to assess.

“All right. Let’s move on,” he said.

Mapping the damage in Yarmouk would require several weeks more for the volunteer engineers in the Yarmouk Committee for Community Development. But the work is seen as vital in reviving a once thriving community.

Successive waves of fighting and airstrikes, not to mention the looting that inevitably followed, had left around 40% of the camp’s 520 acres damaged or destroyed. Vital services like electricity, water and especially sewage are at best intermittent or unavailable. Even now, mountains of rubble — enough to fill 40 Olympic-sized swimming pools, the committee estimates — line almost every street.

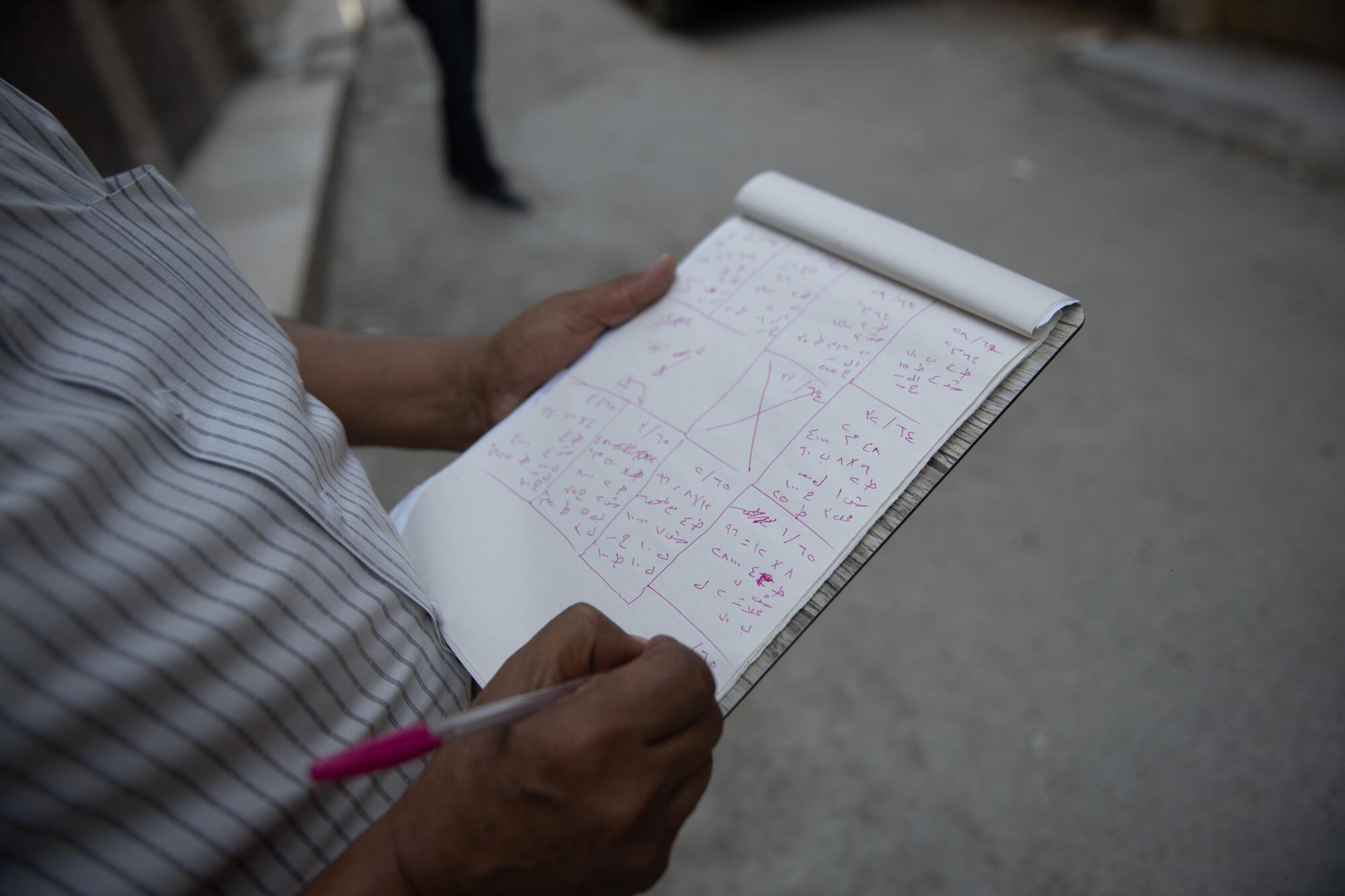

Jamal Al-Khatib, an engineer, takes photographs as he conducts a survey of damaged buildings in Yarmouk, Syria.

(Hasan Belal/For The Times)

“Compared to its size and population, Yarmouk paid the highest price across Syria in terms of damage and hardship,” said Omar Ayoub, 54, who heads the committee and was coordinating with Al-Khatib, Ali and other engineers on the assessment. Though large swaths of Yarmouk are still in ruins, conditions are now “five stars” compared with nine months ago when then-President Bashar Assad fled the country, Ayoub said.

Still, people have been slow to return. Only 28,000 people have come back, 8,000 of them Palestinians, according to Ayoub and aid agencies. For them and the tens of thousands still hoping to come back to Yarmouk, the concept of “home” — whether here or in places their families left behind after the 1948 war and Israel’s founding — has never seemed so far away.

“It used to feel like a mini-Palestine here. Streets, alleyways, shops and cafes — everything was named after places back home,” Ayoub said.

“Will it come back? Life has changed, and the war changed people’s convictions on the issue of Palestine.”

That image of how life in Yarmouk once was drew Muhyee Al-Deen Ghannam, a 48-year-old electrician who left the camp in 2013 for Sweden, to visit last month. He was exploring the idea of bringing his family back, but the landmarks he once used to locate his apartment were all gone. He eventually found it, still standing, but stripped of anything of value.

“Living here, you had such a strong connection to Palestine, and yet we never felt like foreigners in Syria,” Ghannam said.

1. Years of warfare have devastated most streets in Yarmouk, Syria.

2. A construction worker labors in Yarmouk. Few of the former residents have returned to the camp.

3. A girl and her mother visit the grave of a relative in the Yarmouk cemetery amid the devastation caused during the Syrian civil war.

He won’t be leaving Sweden. “I was planning on staying [here]. But with kids, it would be very difficult.” His 16-year-old, he added, hoped to study aeronautics — an impossibility in Syria.

Many others were forced back to Yarmouk by sheer economics, including Wael Oweymar, a 50-year-old interior contractor who returned in 2021 because he could no longer afford rent in other Damascene suburbs. He spent the last four years fixing up not only what remained of his apartment, but its surroundings.

“What could I do? Just give up and have a heart attack?” he said, cracking an easy smile.

“You see this street?” he said. “I swept this whole area myself. There was no one here but me — me and the street dogs. But when people saw things improving, it encouraged them to return.”

Oweymar counted that a victory.

“It was systematic, all this destruction. The intention was to make sure Palestinians don’t return,” he said, echoing a common suspicion among Yarmouk’s residents, who believe the Assad-era government planned to use the fighting to displace Palestinians and redevelop the area for its own use.

“But they destroyed and we rebuild,” Oweymar said. “We Palestinians, we’re a people who rebuild.”

Oweymar’s words were a measure of the uneasy relationship the Assad family maintained with Palestinians. Compared with Palestinian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon, those in Syria — now estimated to number 450,000 — were treated well. Though never granted citizenship, they could work in any profession and own property. Under the rule of Assad’s father, Hafez, Palestinians enlisted in a special corps in the military called “The Liberation Army.”

1. In Yarmouk, it’s common to see buildings missing walls or roofs. Many are pockmarked by bullets or scrapnel.

2. Yarmouk once had 1.2 million residents. Estimates say about 28,000 people live there now, 8,000 of them Palestinians.

3. Amid some rubble lies the burnt and torn image of Ahmed Jibril, the onetime secretary general of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – General Command.

Factions, such as the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine and Hamas, opened training bases in the country and administered camps. At the same time, Syrian security services pursued Palestinians with the same diligence they showed toward homegrown dissidents.

Assad continued his father’s policies and aligned Syria with the so-called Axis of Resistance, an Iran-backed network of factions arrayed against the U.S. and Israel that championed the Palestinian cause. Yet more than 3,000 Palestinians were imprisoned during the civil war — only a few dozen emerged alive.

“Assad became the standard bearer for Palestinian resistance, putting it above anything he did for Syrians. But he also slaughtered Palestinians in huge numbers. We never knew where we stood with him because of that duality,” Ayoub said.

When the civil war began, a miniature version played out in Yarmouk. Some factions insisted on neutrality, while others sided with Assad or the rebels against him. The Syrian military laid siege while the factions duked it out inside Yarmouk.

Neighborhoods became run-and-gun front lines; fighters punched holes through buildings’ walls to avoid ubiquitous sniper fire. In 2015, jihadists from the Islamic State seized the camp. As the battle stretched on, so did the siege, with rights groups estimating at least 128 people died of starvation. Ayoub, now a portly scriptwriter with an avuncular smile, weighed a mere 66 pounds during the siege.

“We had more people die here because of hunger than Gaza,” Ayoub said, referring to the enclave where Israel has mounted a blockade that aid groups warn has resulted in famine.

“Our ultimate dream was to eat our favorite food before we died. One neighbor, I remember, he was craving a French fry — just one,” Ayoub said, a wan smile on his face at the memory.

Mohammad Ali, 63, is one of the engineers working to survey the damaged buildings and assess their needs for future reconstruction in Yarmouk.

Islamic State was finally pushed out in 2018, but Assad’s forces, including regular military units and allied factions, pillaged whatever hadn’t been destroyed, even setting fires inside homes to pop tiles off of walls. They ripped out toilets, window frames and light switches and sold the copper wiring.

Eight months since Assad’s ouster, there is little clarity on what stance Syria’s new authorities will take regarding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Many officials say Syria is in no condition to engage in a fight with Israel, and that it has already paid enough for its advocacy for Palestinians. The U.S., meanwhile, has brokered high-level contacts between Israeli and Syrian officials, and conditioned assistance on the new government suppressing what the U.S. classifies as “terrorist organizations,” including a number of Palestinian factions.

There are already signs Damascus has moved to fulfill those demands.

Abu Bilal, a member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine who gave his nom de guerre because he was not allowed to speak to the media, still minds the party headquarters in Yarmouk. Though the group remained resolutely neutral during the civil war, after Assad fled, gunmen affiliated with the new authorities confiscated the group’s weaponry and training camps.

“Their message was clear: No political activity or military displays. We can only engage in social work or academic research,” he said.

Palestinian factions aligned with Assad came for harsher treatment, he added. Many of their leaders have left the country, and institutions linked to the groups — such as hospitals, newspapers and radio stations — have been seized.

A building damaged during the 14-year Syrian civil war forms a backdrop for a cemetery in Yarmouk, once a thriving Palestinian camp.

None of that elicits sympathy from Al-Khatib and Ali, both of whom served in their younger days in the Liberation Army.

“All the [Palestinian] factions should have stayed neutral and blocked any side, Assad or the rebels, from entering. Had they stayed united, they would have protected the camp,” Al-Khatib said.

He waved at the landscape of destruction before him.

“Now Palestinians are more impoverished than ever. All the factions did was destroy the economic infrastructure in Yarmouk,” he said.

He paused before the fire-scorched carcass of what appeared to have once been a furniture shop.

“See the burns here?” Ali said. “You can tell they’re from looting, not war damage. But since we don’t know how long it burned, we don’t know if the concrete is affected.”

Al-Khatib looked at the scorch marks on the ceiling then shook his head at the ruins before him.

In recent weeks, more nations have said they would recognize a Palestinian state, but here there are more immediate worries.

“What time do we have now to think about or fight for a state?” Al-Khatib asked. “Our only concern is securing our homes.”