Santosh Gupta

Santosh Gupta“My heart is filled with so much pain. Even today, I cry when I think about how that one encounter destroyed my life.”

The year was 1992. Sushma* said she was 18 when a man she knew took her to an abandoned warehouse under the pretext of watching video tapes. There, six to seven men tied her up, raped her and took photographs of the act.

The men belonged to rich, influential families in Ajmer, a city in the western Indian state of Rajasthan.

“After they raped me, one of them gave me 200 rupees [$2; £1] to buy lipstick. I didn’t take the money,” she said.

Last week, 32 years later, Sushma saw a court convict her rapists and sentence them to life imprisonment.

“I am 50 years old today and I finally feel like I got justice,” she said. “But it cannot bring back all that I have lost.”

She said she had endured years of slander and taunts from society because of what happened to her, and both her marriages ended in divorce when her husbands discovered her past.

Sushma is one of 16 victims – all schoolchildren or students – who were raped and blackmailed by a group of powerful men in different places in Ajmer city over several months in 1992. The case became a massive scandal and sparked huge protests.

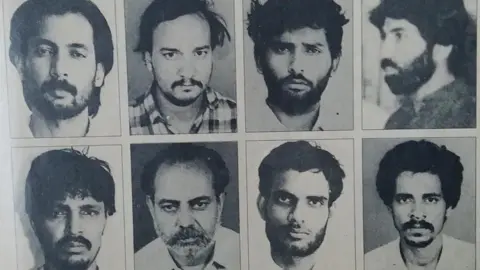

Last week, the court handed out life sentences to six of the 18 accused: Nafis Chishty, Iqbal Bhat, Saleem Chishty, Sayed Jamir Hussain, Naseem – also known as Tarzan – and Suhail Ghani.

They have not confessed to the crime and their lawyers said they will appeal the verdict in a higher court.

Santosh Gupta

Santosh GuptaSo what happened to the remaining 12 accused?

Eight were sentenced to life in 1998, but four were acquitted by a higher court, and the others had their sentences reduced to 10 years.

Of the remaining four, one died by suicide. Another was sentenced to life in 2007 but was acquitted six years later. One was convicted in a related minor case but later acquitted, and one of the accused is still absconding.

“Can you even call this [the 20 August verdict] justice? A judgement is not justice,” said Santosh Gupta, a journalist who had written about the case and has appeared as a witness for the prosecution.

It is a thought echoed by Supreme Court lawyer Rebecca John, who called it yet another case of “justice delayed is justice denied”.

“This points to a problem that extends far beyond the legal system. Our patriarchal society is broken. What we need is a mindset change, but how long is that going to take?”

The accused men used their power and influence to deceive, threaten and lure their victims, said prosecution lawyer Virendra Singh Rathore.

They took compromising photographs and videos of their victims and used them to blackmail them into silence or bring in more victims, he added.

“In one instance, the accused invited a man they knew to a party and got him drunk. They took compromising photos of him and threatened to make them public if he didn’t bring his female friends to meet them,” he said. “That’s how they kept getting victims.”

The accused also had strong political and social connections. Some of them were associated with a famous dargah (Muslim religious shrine) in the city.

“They roamed around on bikes and cars in what was a small-town city at the time,” Mr Gupta said. “Some people were afraid of these men, some wanted to get closer to them and some wanted to be like them.”

He said that it was their power and connections that had helped keep the case under wraps for months. But there were people – like those working at the studio where the photos were developed and even some police officers – who were aware of what was going on.

One day, some of the photographs taken by the accused reached Mr Gupta. They had a chilling effect on him.

“Here were some of the city’s most powerful men committing heinous acts with innocent, young girls – and there was proof of it. But there was no major reaction from the police or the public,” he said.

He wrote a few reports about it but none managed to blow the case wide open.

Then one day, his paper “made a daring decision”, he said.

It published a photo that showed a young girl, naked to the waist, pressed between two men who were fondling her breasts. One of the men was smiling at the camera. Only the girl’s face was blurred.

The report sent shock waves through the city. The public was outraged and shut the city down in protest for days. Anger spread through Rajasthan like raging fire.

“Finally, there was some concrete action from the government. Police registered a case of rape and blackmail against the accused and it was handed over to the the state’s Criminal Investigation Department [CID],” Mr Rathore said.

Santosh Gupta

Santosh GuptaMr Rathore explained that the trial had dragged on for 32 years because of several factors, including the staggered arrests of the accused, alleged delaying tactics by the defence, an underfunded prosecution and systemic issues within the justice system.

When police filed the initial charges in 1992, six of the accused – who were only convicted last week – were left out because they were absconding.

Mr Rathore believes this was a mistake, as when the police finally filed charges against the six in 2002, they were still on the run. Two of them were arrested in 2003, another in 2005 and two more in 2012, while the last one was apprehended in 2018.

Every time one of the accused was arrested, the trial would begin afresh with the defence recalling victims and witnesses brought by the prosecution to give their testimonies.

“Under the law, the accused has the right to be present in court when witnesses are testifying and the defence has the right to cross-examine them,” explained Mr Rathore.

This put the victims in the horrifying position of having to relive their trauma over and over again.

Mr Rathore recalled how often the victims, who were now in their 40s and 50s, would scream at the judge, asking why there were being dragged to court, years after they had been raped.

As time passed, the police also found it challenging to track down witnesses.

“Many didn’t want to be associated with the case as their lives had moved on,” Mr Rathore said.

“Even now, one of the accused is absconding. If he is arrested, or if the other accused appeal against the verdict in a higher court, the victims and witnesses will be called to testify again.”

Sushma – who was one of three victims whose testimony played a key role in convicting the six accused – said that she had been talking to the media about her ordeal because she was telling the truth.

“I never changed my story. I was young and innocent when these people did this to me. It robbed me of everything. I have nothing to lose now,” she said.

*Name has been changed. Indian laws do not allow the identity of a rape victim to be disclosed.