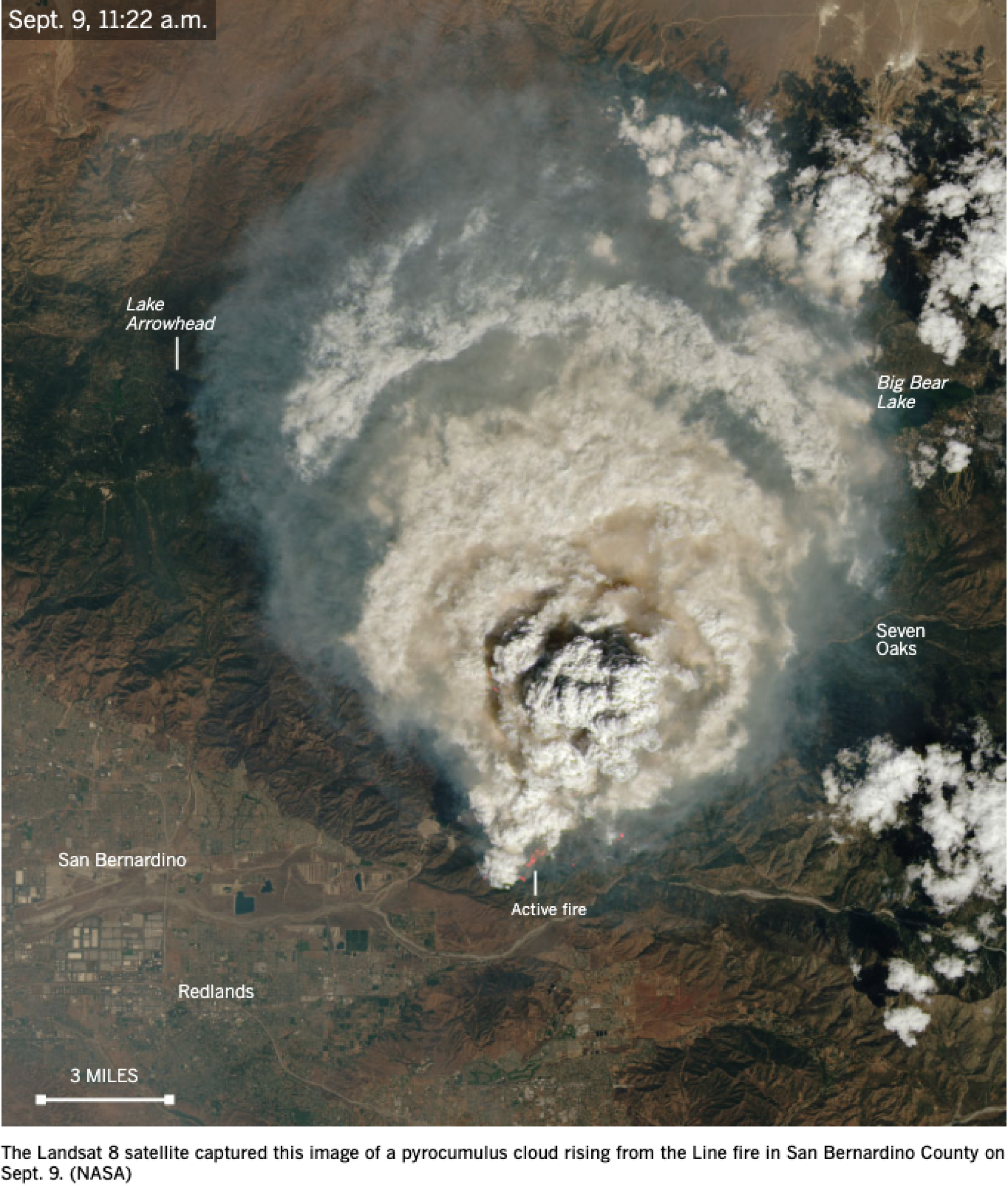

The first full weekend of September, with the Line fire 20,000 acres in size and only 3% contained, a resident of San Bernardino County described the sky as looking “exactly like a nuclear warhead had been set off.”

On a basic level, this makes sense: By that point, the Line fire had already released more energy into the atmosphere than a dozen atomic bombs. And just as nuclear blasts produce a distinctive mushroom cloud, uncontrolled wildfires can be powerful enough to generate their own weather.

When wood and other vegetation combust, it they produce four main compounds: carbon dioxide, smoke (itself a mix of toxic ingredients like carbon monoxide, methane, benzene and many more), heat and water vapor. Of those, carbon dioxide is the least relevant to the local weather — while it plays a major role in the global climate, that is more because of its long lifespan rather than its immediate potency.

The most notable consequence of smoke emission is its dangerous effects for human health.

A plume of smoke can extend hundreds or thousands of miles as it’s carried by wind currents. In addition, smoke aerosols block and scatter sunlight, causing the surreal “red sun” effect that shows up in apocalyptic-seeming pictures on social media; their optical properties also tend to suppress precipitation in downwind locations, which may (in the long term) fuel more fires because of drier conditions.

Billowing smoke from the Line fire, right, and Airport fire, left, obscure the sun and turn the sky an apocalyptic hue of orange.

(Gina Ferazzi/Los Angeles Times)

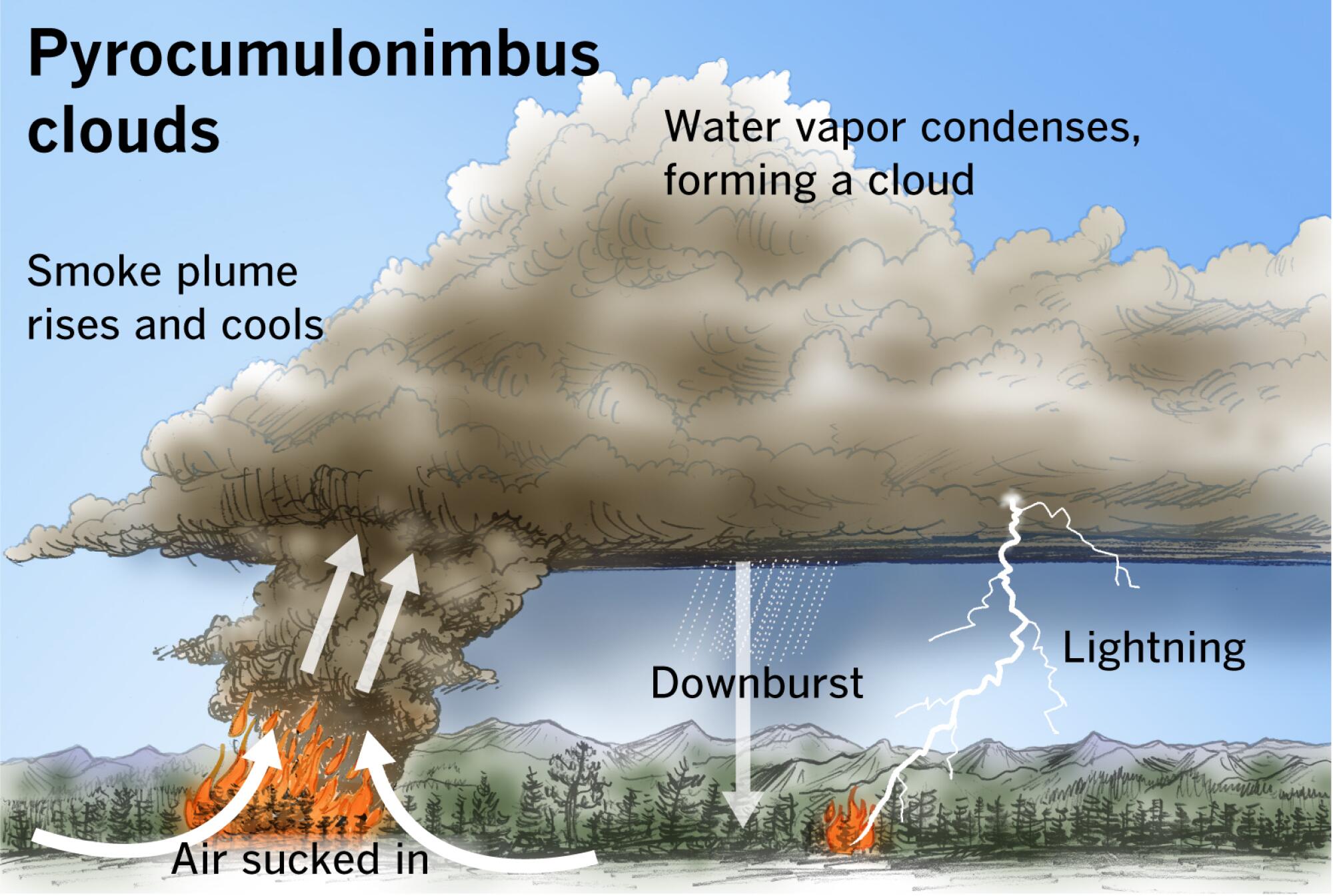

The next byproduct of fire is heat — like the burner in a hot air balloon, the wildfire causes the bottom layer of the atmosphere to become less dense and therefore rise. As the air over the fire is lifted, air from the outside rushes in to replace it, thereby supplying the fire with the oxygen that allows it to continue burning.

If the fire is powerful enough, it can produce a “firestorm.” This occurs when all the winds surrounding a conflagration are directed toward the fire’s center, leading to a feedback effect: more oxygen produces more intense flames, which in turn pull in even more oxygen.

These winds have a mixed effect on the fire’s ability to spread — on the one hand, the gusts are directed inward, meaning that sparks are less likely to be pushed outward. On the other hand, the strong updrafts can catch hold of burning embers, lofting them into unburned material, where they can produce “spot fires” up to several miles away from the fireline.

Moreover, a firestorm can radiate heat so intense that it becomes impossible for firefighters to operate in its vicinity. Firestorms have been observed not only during wildfires but also during World War II when bombed cities — such as Dresden, Germany, and Hiroshima, Japan, —experienced far more destruction from resultant fires than from the initial bombing.

The final ingredient is water vapor.

As the hot air rises higher in the atmosphere, the water vapor released by combustion will condense, aided by the presence of smoke particles that act as “condensation nuclei” and allow the water to form droplets. This condensation produces more heat, leading to even more powerful convection, and the end result is known as a pyrocumulus (or, in more extreme cases, pyrocumulonimbus) cloud.

These clouds often signal trouble for firefighters trying to contain the blaze — not just because they indicate that the fire is gaining strength, but also because the dangerous conditions and low visibility within the cloud prevent the use of aircraft to fight the fire. In addition, these clouds can produce frequent lightning strikes, which ignite new fires in the area.

One saving grace is that the pyrocumulus clouds can produce rain, which in some cases will suppress the very fire that created them. However, depending on wind conditions, this rain sometimes evaporates before it reaches the ground because of the hot, dry environment surrounding the fire.

If this occurs, it can produce a “downburst” as cold, dense air descends rapidly out of the cloud. Just like the updrafts, this feeds the fire with fresh, oxygenated air; unlike updrafts, downbursts cause gusts that billow out away from the center of the fire, leading it to spread rapidly in multiple directions at once.

A pyrocumulonimbus is the ultimate extreme pyrocumulus cloud.

(Paul Duginski / Los Angeles Times)

What does all this mean for Southern California?

Fortunately, large-scale firestorms are almost unheard-of in the area, in part because the region’s narrow canyons and strong prevailing winds act to direct gusts — and therefore fires — in specific directions. Less fortunately, both factors can act to speed fire spread and promote pyrocumulus formation.

Structures on the top of hills and ridges are at heightened risk, since fires can move up to eight times faster when they are climbing steep slopes than they do on flat land, and lightning strikes from pyrocumulonimbus clouds are more likely to strike elevated locations.

With the National Interagency Fire Center predicting above normal fire potential along the Southern California coast through the end of the year, there is a strong likelihood that more fires are on the way for the region in the coming months.

The feedback between wildfires and their environment can cause rapid and unpredictable shifts in the fires’ direction and intensity, so it is vital for residents to remain alert during high-risk periods.